I awoke with cramped muscles from sharing my narrow couch with Lenny. As I watched the dust motes lazily circling through the light around his curly hair I thought, “I gotta get rid of this guy.”

cramped muscles from sharing my narrow couch with Lenny. As I watched the dust motes lazily circling through the light around his curly hair I thought, “I gotta get rid of this guy.”

I blinked in self-astonishment, jumped up and put on the coffee. Get rid of Lenny? The thought was preposterous—in just one month with him I’d acquired a taste for Far Eastern cooking, experienced the magic of midnight ferry rides, learned to play chess, and had been introduced to Zen Buddhism, bird watching, and camping in the woods. His pile of possessions neatly stacked in a corner of my studio apartment was small price to pay. I sipped my coffee and watched him sleep, his slender form framed by the elegant lines of the Japanese style sofa. It was about eight feet long, and just wide enough to accommodate one average-sized body. Graceful black and gray leaf shapes swirled against a backdrop of off-white linen; the back and arms were a rich, deep ebony. Lenny’s porcelain skin pulled taut over finely sculpted bones were the perfect adornment for my furniture. Still, I did not want to continue sleeping with his feet in my face.

No, the couch would have to go, to be replaced with sleeping accommodations for two, and good riddance to its memories. It was outrageously decadent anyway, unsuited to my new lifestyle. Perhaps I had once found it beautiful, but now it seemed an affront, a reminder of the room from whence it came, an orange room decorated in suburban Japanese. The room in turn reminded me of the sprawling ranch house it had been part of, and the life that house had sheltered. My ex-husband and I had made love on the couch, first covering it with a clean sheet…yes, the couch must go. Definitely. Today.

Lenny stirred and threw an arm over his eyes to deny morning. I knelt by his side and embraced his face with my eyes. I never tired of looking at that face: the high fine cheekbones, the haunted haunting eyes, the full lips revealing the faintest droop of disillusionment. An old man had once described Lenny as aristocratic.

“Aristocratic orphan,” I murmured, brushing the hair from his forehead.

“Huh?” Lenny put his arm down to look at me. He always looked at me as if he couldn’t quite believe I was real.

“Lenny, listen,” I began, eager to spring into action, “I have a great idea. Let’s get rid of this couch and buy a big foam mattress.”

“Oho!” He sat up and pulled on his threadbare trousers.

“Why oho?”

He looked sideways at me. “Janbaby, you are as transparent as cellophane. Let’s get rid of the couch! Ha ha!”

I stared at him, genuinely puzzled.

He reached over and rumpled my hair with affection. “So, you can’t stand the memories anymore, huh? Time to clear the room of old ghosts? It’s okay, babe, I can dig it.”

I smiled uncertainly; he was partly right, but I resented his quick analysis, that way he had of pinpointing and defining my emotions. “Actually, the main reason is my muscles hurt from sleeping in such a tight space.”

“Whatever you say, baby. You say the couch gotta go, it goes.”

I barely managed to restrain myself from saying, “Of course — it’s my couch!”

One of the outstanding features of this couch was that it did not fit in the building’s elevator. Three moving men had labored three sweaty hours maneuvering it up and around the narrow stairwell twelve flights to its destination. My ex-husband had been on hand, presumably to ease my transition into urban singlehood.

“Jan,” he reprimanded me as if the whole thing was my fault, “these guys scratched the finish on the couch.”

“David, cut it out. Look what they’re going through with it.”

“I think you oughtta take $20.00 off their bill.”

“How can I complain about a few scratches when these guys nearly killed themselves moving it?”

“That’s so typical of you—you’re always being taken. I don’t know how you’re gonna survive without me.”

“I’ll do just fine, don’t you worry.”

“Yeah, I can just see you a month from now. Some bum will come along, find out about your inheritance and use you as a meal ticket.”

“David, please, I would like you to leave my apartment. Now.”

“If it hadn’t been for my dumb mother leaving you half her estate, you wouldn’t even have this apartment.”

“Your mother wasn’t dumb—she knew you were unbearable and she felt guilty towards me, so she gave me a ticket out.”

Angry, David reached the door as the moving men staggered in with the last of my possessions. “You guys oughtta make good for the scratches on the couch,” he said, before disappearing down the hall. They glared at him.

“Don’t pay any attention to him,” I said, handing each one a hefty tip to compensate.

Considering the moving hassles a prospective buyer would face, I decided to ask only $500 for the couch even though I’d paid $3000 for it just two years ago. I placed an ad in the Village Voice.

She said her name was Margaret Smith, and with a perfunctory glance at the couch seated herself upon it. She then proceeded to confess bits and pieces of her jagged life. I yawned, annoyed by Lenny’s interest in her story. After she’d gone through two abortions and numerous lovers, I asked, “Do you want the couch?”

“What? Oh, yes, the couch. Well, of course.”

“Jan’s a little anxious,” Lenny told her, embarrassed by my businesslike manner. “She can’t stand the sight of her ex-husband anymore.”

I glared at him. Margaret Smith gave him a knowing smile, then turned to me. “I know what it’s like, but you really should talk about it. There’s nothing to be ashamed of—we all have exes.”

“It doesn’t fit,” I said.

“What doesn’t fit?”

“The couch. It doesn’t fit in the elevator. It has to be carried down–you’ll need a few guys to help you.”

“Oh, that’s no problem. My two boyfriends will do it. It”s just marvelous how well they get along. I’m so much better off with the arrangement I have now.”

She talked about her life for another l5 minutes. Finally she left, saying she’d come for the couch on Saturday.

“Boring!” I exploded, banging the door shut behind her.

“Janbaby, why are you so afraid of opening up to people? She was a beautiful chick, honest and up front with everything.”

“Is that really what you think?”

He turned to me, his face free of guile. “Sure. That’s how people should be—trusting. She knew she could trust us.”

“But why? Why should she trust us?”

“Why not? No, seriously, Jan, listen to me: you and me, we’re good people. And this is a New Age. You gotta start accepting and believing in your own goodness.”

He stared at me intently, willing me to accept what he so fervently believed. Suddenly I was ashamed of my cynicism; Margaret Smith was probably a fine human being. I walked into Lenny’s open arms and wept in confusion while he, not for the first or last time, comforted me.

On Saturday morning we left the door ajar while eating breakfast. I was savoring the first cigarette and coffee when a gargantuan man walked in.

“You the people selling a couch?”

“Are you buying it?”

Margaret Smith suddenly emerged from behind the Promethean figure. “This is Bo. Bo, this is Lenny, and—I’m sorry, I forgot your name.”

“Janice.”

Bo bowed his head formally. “Pleased to meet you, Janice. Leonard.”

Lenny turned into Super Host, transferring the contents of the refrigerator onto the table, pulling off lids, putting out dishes and silverware.”Bo, baby, try some of this cheese. Can I get you a beer? Coffee?”

“Where’s…” I began, looking around for Margaret’s other boyfriend. She quickly cut me off.

“Now, I’m sure there won’t be any trouble moving this couch. You look like a big strong fella.” She looked coyly at Lenny; if she secretly thought her chosen adjective incongruous, she didn’t show it. What a fool, I thought, for I knew that Lenny really was a “big strong fella.” I’d seen him split wood with those delicate hands, had felt his hard body on top of mine. I decided to sit back and watch the day’s drama unfold. It was anyhow beyond my control.

My strong fella looked at me, his eyes twinkling. “I knew I’d get roped into this!” he said with a good-natured laugh.

“Let’s stop this partying and get to work,” Margaret ordered. “I’ve been thinking about the situation. It seems to me that with a little ingenuity we could get this couch into the elevator.”

“Watch out for her,” Bo warned with a belly laugh.

“Bo! You promised to cooperate.”

“It doesn’t fit,” I said.

“We will make it fit. Now, Bo, just examine this couch and see what you can do. I need a cup of coffee.” Bo stood, looking awkwardly helpless, while Lenny took out a tape measure and crawled behind the couch. Then he dashed out to the elevator with his tape. “Nope,” he reported cheerily when he returned, “it doesn’t fit.”

“What if you took off the legs?” Margaret suggested.

Lenny crawled underneath the couch and emerged covered with dust, a sight that just a few short months ago would have mortified me. “We’ll need a Phillips head screwdriver. Come on, Janbaby, walk me to the car.”

“Lenny,” I told him on the way to the car, “these people were supposed to move the couch by themselves. That’s why I’m selling it so cheap.”

“Yeah, I know — this Bo is a rip. But what the hell, what else do we have to do today?”

When we returned to the apartment music was blasting from the stereo and Bo sat cross-legged in a corner reading my yoga book.

“Are you two into yoga?”

“Oh, yeah, sure.” Lenny nodded gravely.

This was news to me; I practiced nearly every morning, but I’d never seen Lenny take so much as a deep breath, much less invert his body in a shoulder or head stand.

“Come on, boys,” Margaret barked, clapping her hands. Let’s get this show on the road.” Lenny took off the sofa legs, losing maybe three inches of its height. He and Bo dragged it into the hall and rang for the elevator.

First they shoved it in straight. Then they stood it on end. Then they tried various diagonal positions. In every case, the couch wouldn’t clear the elevator doors. Finally, huffing and puffing, Lenny announced, “It doesn’t fit.”

“It doesn’t fit,” Bo repeated.

“I told you so.”

“Now that we all agree,” said Margaret, “let us proceed to the stairwell.”

Bo took up the rear while Lenny carried most of the weight up front. I navigated. Margaret Smith remained upstairs.

Lenny labored under the weight of the couch, his face flushed and hair damp with sweat, while Bo cooly held up his end, more or less pushing it onto Lenny’s back. I trailed behind, in case they needed me to open a door or something. When we finally reached the lobby, Bo went back upstairs to get Margaret, who brought her car around to the front of the building. With heavy twine Lenny did a Boy Scout quality job of tying the couch to the roof of the car.

“I left a check on the table,” Margaret called as they drove off with my couch. I’d been so captivated by the day’s mini-drama, I’d forgotten about the money. I raced upstairs and was relieved to find she had indeed left a check.

On Monday I deposited the check. On Tuesday I received the following letter:

Dear Janice, Unfortunately the couch broke in half as we were driving it home due to the slipshod way in which it had been tied to the roof of the car. I cannot afford to pay for something I do not have, and so I am stopping payment on my check. Yours, Margaret Smith.”

Against Lenny’s protests I went to Small Claims Court and issued a summons. It was returned marked “Addressee Unknown.”

For nearly a week we slept on the floor. Lenny, accustomed to far worse accommodations, didn’t mind, but I was sore and grumpy. We finally went down to 14th Street, where we purchased a lightweight mattress, rolled it up and tied it with string and took it home on the subway. We put it down in a corner and threw a madras bedspread on top. Now we had plenty of room, and I slept soundly—until, a few nights later, when I awoke screaming from a nightmare in which my pocketbook and identification had been stolen from me.

“Wake up, Jan, it’s only a dream.” Lenny turned on the light.

I stared at him. His features appeared distorted, almost wolfish. I screamed louder.

“What is it, baby? Tell me.”

“I want my couch back.”

“You sold it.”

“I didn’t sell it, I threw it away. And you helped me.”

“Janbaby, take it easy. What’s this really about?”

“I want my couch back!”

“Jan, you can’t go back.”

“Can the jargon, Len. This isn’t about ‘going back’ or any deep psychological illness. I’m buying a new couch tomorrow exactly like the old one, if I have to search the whole city to find it.”

“Fine. You want a new couch, we buy a new couch.”

“What is this ‘we’?” I spat out. “It’s my money.”

This was a simple statement of fact, but the viciousness behind it said volumes about the feelings beneath. Suspicion and resentment of Lenny dripped from my lips; his facial muscles twitched as if hit. A tense silence enveloped us as he lowered his head. When he raised it again his lips were drooped and tears swam in his hazel eyes. He didn’t have to say a word; I was filled with remorse for having wounded him over a material possession. Over money, that thing we swore was the root of all evil.

I put my arms around him. “It’s okay, Lennybaby, it’s okay. I didn’t mean it, about the money. It’s all right, baby, everything’s all right.”

I cradled his head close to my breast and gently rocked him to sleep. When dawn broke we were still in that position, my body shielding Lenny’s eyes from the glare of the morning sun.

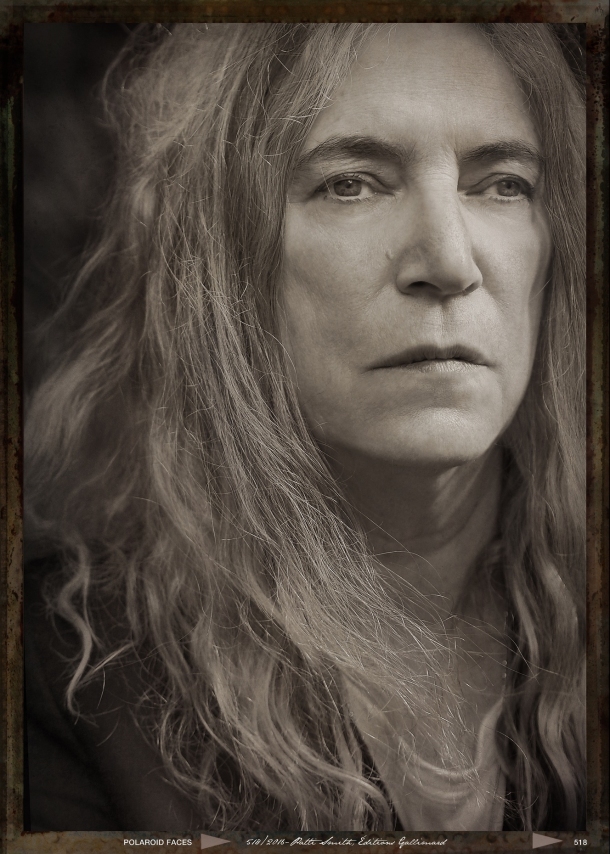

Devotion: Why I Write

Devotion: Why I Write Smith retired more or less from public life with her husband Fred, had two kids, and stayed home to raise them–getting up early each day to write. In a recent interview with Alec Baldwin she says that she loved her life at that time, and the continual writing served to hone her craft. She said she couldn’t have written the books she’s writing now were it not for those years of practice.

Smith retired more or less from public life with her husband Fred, had two kids, and stayed home to raise them–getting up early each day to write. In a recent interview with Alec Baldwin she says that she loved her life at that time, and the continual writing served to hone her craft. She said she couldn’t have written the books she’s writing now were it not for those years of practice.

According to my friend Rita, the invention of the blender spelled disaster for the potato latke. She insists that the blood dripping from our grandmothers’ knuckles as they grated the potatoes is what made their latkes so delicious.

According to my friend Rita, the invention of the blender spelled disaster for the potato latke. She insists that the blood dripping from our grandmothers’ knuckles as they grated the potatoes is what made their latkes so delicious. cramped muscles from sharing my narrow couch with Lenny. As I watched the dust motes lazily circling through the light around his curly hair I thought, “I gotta get rid of this guy.”

cramped muscles from sharing my narrow couch with Lenny. As I watched the dust motes lazily circling through the light around his curly hair I thought, “I gotta get rid of this guy.”

Cracked and broken sidewalks

Cracked and broken sidewalks